Calculating driving distances using Open Source Routing Machine

A guide to running Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM) on AWS

A while back I found myself needing to calculate driving distances and times between 30,744 origins and 408 destinations in the continental US. That’s a total of more than 12 million routes on a huge network! Ordinarily something like Google’s Directions API would be helpful, but with the volume of routes and my grad student research budget this was not an option.

Thankfully there’s a great product out there called Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM) that I was able to use for the task. Given the size of the road network I needed for my task, I did need to make use of virtual computing to run OSRM; however, I was able to do so at a tiny fraction of the cost of Google’s Directions API. Open-source for the win!

Getting started took quite a bit of learning-by-doing. To provide positive learning-by-doing spillovers, I thought I would provide a brief

Most applied researchers are likely interested in calculating driving distances and times for relatively large geographies. OSRM enables shortest path computation on continental-sized road networks; however, to do so requires sufficient memory and disk size and can take time to setup. If you are interested in, for example, calculating drive distances and times for the continental U.S., it is unlikely that you will have the technical requirements to do so locally. That’s why running OSRM on an AWS EC2 instance is a natural solution that adds minimal cost; fixed costs of learning how to use AWS aside, this is still far less expensive when running a large number of routes than paid services.

I outline the complete process that I took to calculate drive distances and times for a complete matrix of origins and destinations in the continental U.S. via and AWS EC2 instance. Some or all of the below steps may or may not apply to you—free disposal of course applies so please use whatever is helpful in your application. Even if you, say, choose to use an alternative remote computing approach, the same general formula should still apply:

- Set up your remote instance (via AWS, etc.)

- Set up the OSRM server for your desired road network

- Run your queries!

A few additional disclaimers. I am using a Mac running Mojave; if you are using a different operating system, the processes for accessing your AWS instance are likely to be different (thankfully AWS has ample documentation). I also made specific decisions on how to go about setting up the OSRM server on my instance—e.g., running a Linux OS on the instance, building OSRM using a Docker image, etc.—which are by no means the only way to go about doing this. I outline my rationale below, but alternative approaches may be better for your own purposes. Hopefully this resources is useful in your projects; if you have any questions, feel free to contact me by email.

Setting up your AWS instance

For my project calculating continental U.S. drive distances and durations, I ran the OSRM server on the entire U.S. road network (a very large network; the *.pbf file—more on this below—is 7.2 GB). To make sure that I had more than enough memory, I set up an m4.10xlarge instance. Generally, I think that an M4 instance is a good choice for this kind of task; AWS says that they provide a balance of compute, memory, and network resources. Your choice of a specific instance should depend on your memory/virtual CPU requirements. The table below shows the different M4 configurations (the full set of instance types is available here).

| Instance | vCPU | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|

| m4.large | 2 | 8 |

| m4.xlarge | 4 | 16 |

| m4.2xlarge | 8 | 32 |

| m4.4xlarge | 16 | 64 |

| m4.10xlarge | 40 | 160 |

| m4.16xlarge | 64 | 256 |

AWS offers two pricing schemes which depend on how you choose to schedule your EC2 usage: on-demand instances which allow you to use your instance whenever you like versus spot instances which allow you to make requests for spare EC2 computing capacity. You end up getting up to 90% off if you go the spot instance route. Additional info on pricing is available here.

Once you’ve decided which instance type and a pricing option is best for your project, the next key decision is which operating system you want to run on your instance. This will have important implications for implementing the steps that follow. I had my instance run the Amazon Linux AMI; this is the default and running Linux was helpful given that a lot of the OSRM backend support is geared towards Linux or Ubuntu OS.

If you’re following the steps in this guide, I would suggest the default Amazon Linux AMI for your instance so that the specific steps included below are relevant to you. Once you’ve chosen an instance type, pricing option, and machine image, you are ready to get your instance up and running. But first you need to set up your key pair. This is the security credentials that you will use to prove your identity/access permissions when connecting to your instance. You can do so by following Amazon’s tutorial for EC2 key pairs and Linux instances: Amazon EC2 key pairs and Linux instances. I would recommend naming your key pair for this project something straightforward, like “osrm-instance” and make sure that you save it to a local directory you can easily navigate to via the command line as a *.pem file.

Rather than copying directly from the AWS guides, here’s the link to a tutorial that walks you through the launch process for the Amazon Linux AMI: Amazon Linux instance setup tutorial.

In step 4 of setting up your instance via the EC2 console, you’ll be asked to customize the elastic block storage with which your instance is launched. I added 128 GB of EBS, but I also ran a few projects using the OSRM server entirely remotely on my instance. This is not necessary if you follow the steps outlined below to run queries locally using the OSRM server you set up on your AWS instance. You will also be asked in step 6 to setup security groups. I would suggest setting up two TCP protocols, both specified to accept traffic from your IP address as the sole source: one standard port 22 protocol and the other a custom TCP protocol for port 5000; it will be important that port 5000 is open to your IP when it comes time to send queries to your OSRM server.

Setting up OSRM

Once your Amazon Linux instance is up and running, it is time to connect to it and begin setting up OSRM. I would encourage you to take a look at the AWS tutorial on connecting to your instance using an SSH client. This can be done from the command line when using Mac OS:

cd ~/directory_containing_pem

ssh -i "osrm-instance.pem" ec2-user@[Your Public DNS]The Public DNS for your instance is available in the EC2 console. An example (expired) Public DNS is “ec2-18-221-51-143.us-east-2.compute.amazonaws.com”.

I think that the easiest way to build OSRM on your instance is to use Docker. The team behind OSRM publish ready to use lightweight Docker images for each OSRM release. This approach has several benefits. First, you don’t need to worry about cloning OSRM backend, which would require you to have a Github account and be prompted to enter your username and password. Using the Docker images also means that you don’t have to install the large number of tools and libraries required to build and run osrm-backend “native” on your EC2 instance. Additional info on the Docker images published by Project OSRM is available on the Project-OSRM/osrm-backend Github page and on the Project OSRM dockerhub page. The OSRM backend Docker images are quite lightweight, so there’s little in the way of a tradeoff in terms of overhead for the ease of use that you get.

To build osrm-backend using the latest published Docker image, first, set up Docker on your EC2 instance (docker docs). After connecting to your instance, you can execute the following steps via the command line to set up Docker:

sudo yum update -y

sudo yum install docker -y

sudo service docker start

sudo usermod -a -G docker ec2-userDocker should now be set up on your instance. You then need to log out and log back in so that your group membership is re-evaluated:

exit

ssh -i "osrm-instance.pem" ec2-user@[Your Public DNS]

docker infoThe final line checks that Docker is up and running. Now that you’re all set with Docker, the next step is to download/upload OpenStreetMap extracts to your instance. There are several ways of doing this, but by far the easiest is to use Geofabrik. Geofabrik offers easy downloads of OSM road networks for pretty much any aggregate geography you could want. In our case, it allows us to bypass downloading OSM networks locally and then uploading them to our instance: you can just fetch the data directly in your instance using the following command-line code:

wget https://download.geofabrik.de/north-america/us-latest.osm.pbfWhere this is fetching the latest OSM network for the entire US (about 7.2 GB). To find the download address for your desired geography, simply look for it on the Geofabrik site.

Once you’ve fetched the relevant road network, it is time to pre-process the network extract. I assume that you are looking for driving directions and times, so we will do so with the car profile. To do so, execute the following commands separately:

docker run -t -v $(pwd):/data osrm/osrm-backend osrm-extract -p /opt/car.lua /data/us-latest.osm.pbf

docker run -t -v $(pwd):/data osrm/osrm-backend osrm-partition /data/us-latest.osrm

docker run -t -v $(pwd):/data osrm/osrm-backend osrm-customize /data/us-latest.osrmThe first line creates an OSRM object from the downloaded road network using the car profile (can also switch to bicycle and walking profiles, but if you’re doing that you probably aren’t using large networks, can run OSRM locally, and don’t need this guide!). The second and third lines create the contraction hierarchies, which facilitate the shortest route between two points. Note that you will have to change “us-latest.osm.pbf” and “us-latest.osrm” in these commands to match the road network you are using. Each of these three commands will take a while to run, and total run time depends on the size of the road network you are using. Running this on the US road network took about 2-3 hours total.

You are now almost ready to send routing queries to your OSRM server. The final step is to start a routing engine HTTP server on port 5000:

docker run -t -i -p 5000:5000 -v $(pwd):/data osrm/osrm-backend osrm-routed --algorithm mld /data/us-latest.osrmThis final step should take a few moments, but at the end you will get the following message: “running and waiting for requests” — you’ve done it! Your OSRM server is up and running and ready to receive queries.

Now that you’ve gone through the process of setting up your instance and getting your OSRM server up and running, you can exit your connection to your instance at any time and return to run additional queries when you want. To do so, simply re-connect to your instance and run the final command above that you used to start your routing engine HTTP server on port 5000.

Running OSRM queries

Now that your OSRM server is up and running, you can test to make sure it is running as expected by navigating to the following URL:

http://your_server_ip:5000/route/v1/driving/13.388860,52.517037;13.385983,52.496891?steps=falsewhere “your_server_ip” will be the Public DNS for your instance. You should get a JSON result if everything is running as expected.

Example R code

To get driving distances and durations for a large set of origin-destination pairs, I used the osrm R package with the OSRM server option set to the IP address of the OSRM server I set up. Specifically, since I needed driving distances and durations from each origin to every destination for 30,744 origins and 408 destinations, I used the “osrmTable” function from the osrm R package, sending calls to the server in batches of 10 origins at a time. I’ve included the R function that I used to implement this as perhaps a helpful starting point for your own project.

# Load packages:

pacman::p_load(data.table, dplyr, tidyr, osrm, parallel, rlist)

# Function to batch generate large driving distance and duration matrices using specified OSRM server:

drive.distance <- function(origin.file, dest.file, chunk.size = 10, server, num.cores = 1, output.dir = NULL) {

# Load origins data:

origin.data <- fread(origin.file)

# Split origins data into chunks:

nr.origin <- nrow(origin.data)

origin.chunks <- split(origin.data, rep(1:ceiling(nr.origin/chunk.size), each=chunk.size, length.out=nr.origin))

# Import destination data:

dest.data <- fread(dest.file)

# Set OSRM related options:

options(osrm.server = server, osrm.profile = "driving")

# Generate duration and distance matrices for each origin and destination pair:

matrix <- mclapply(1:length(origin.chunks), function(x){

osrmTable(src = origin.chunks[[x]], dst = dest.data, measure = c('duration', 'distance'))

}, mc.cores = num.cores)

# Construct duration matrix:

durations <- lapply(matrix, function(x){x$durations}) %>%

do.call(rbind,.) %>%

data.table(.)

durations[,origin.id := origin.data$origin.id]

# Construct distance matrix:

distances <- lapply(matrix, function(x){x$distances}) %>%

do.call(rbind,.) %>%

data.table(.)

distances[,origin.id := origin.data$origin.id]

# If requested, write files to given directory:

if (!is.null(output.dir)) {

output1.filename <- paste0(output.dir, "driving_durations.csv")

output2.filename <- paste0(output.dir, "driving_distances.csv")

fwrite(durations, output1.filename)

fwrite(distances, output2.filename)

} else {

return(list(distances, durations))

}

}

Final product

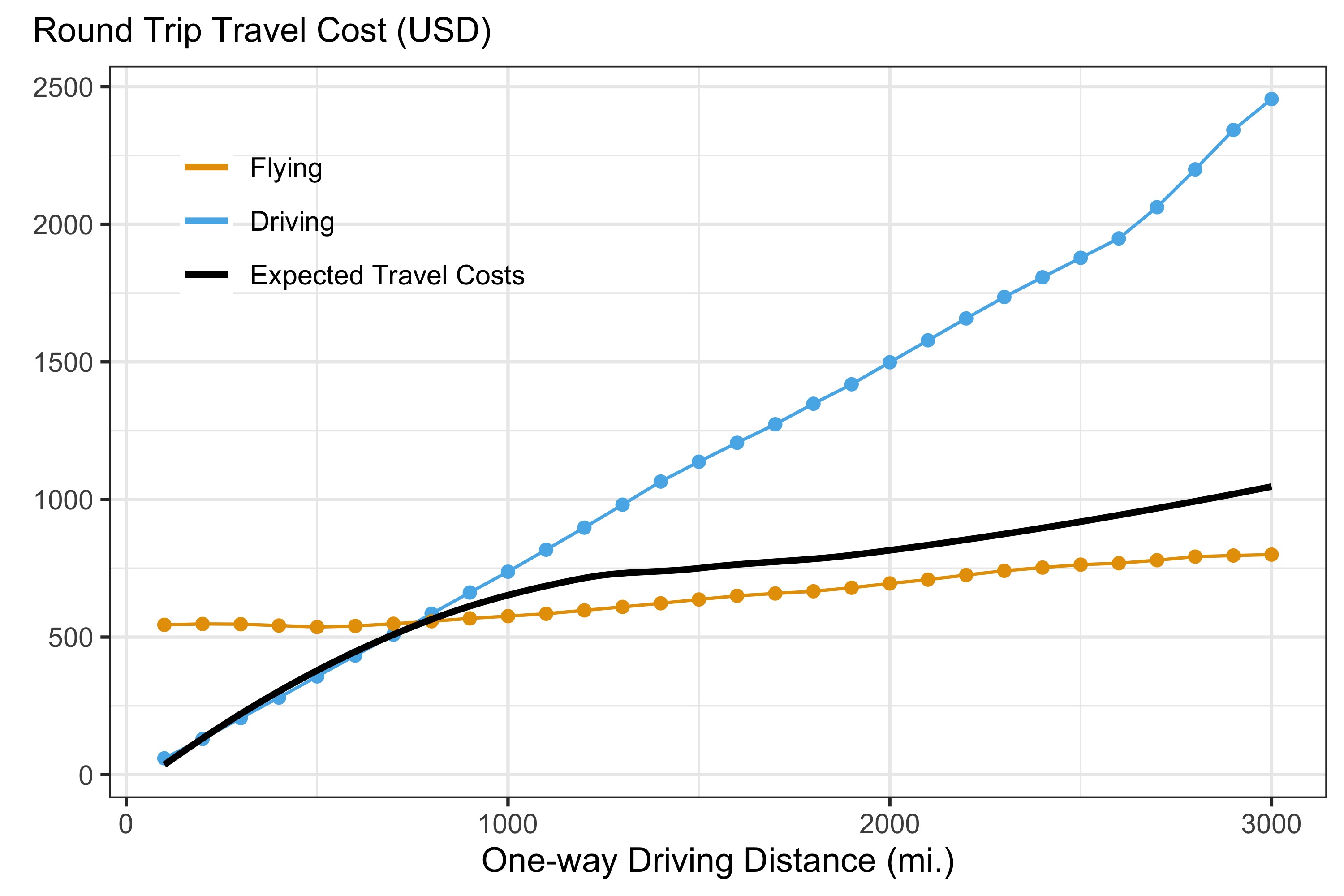

If you made it this far, the least I can do is show you a pretty(ish) picture. Below is the final product. Note that the above steps actually only produced half of the below image—I also needed to calculate expected flight costs for each of my origin-destination pairs which could be the topic of several other blog posts. But anyways, everyone loves a picture!